The status quo jeopardizes wild salmon recovery. That’s what NOAA Fisheries, the federal agency in charge of implementing the Endangered Species Act regarding salmon, told the Federal Emergency Management Agency in reviewing FEMA’s floodplain management plan.

If status quo development, pollution and other ongoing factors damaging and destroying salmon habitat are allowed to continue, ESA-protected species such as threatened Puget Sound chinook and steelhead will not recover.

That means we need to take a hard look at how we’re doing when it comes to salmon habitat protection and restoration. For us, salmon recovery is about more than the ESA, it’s about our treaty rights, our culture, our economies and our very existence.

We are 10 years into recovery efforts for ESA-listed Puget Sound chinook. We know we can’t make up for lost and damaged habitat by further cutting harvest or producing more hatchery fish. We must focus on habitat.

We have accomplished great things on the habitat front in the past few years. Dikes have been torn down and hundreds of acres of estuary habitat have been created at the mouths of the Nisqually and Skokomish rivers. The Lummi Nation is reconnecting tidal channels and restoring hundreds of acres of estuary habitat up in Bellingham Bay. The Quinault Indian Nation is restoring the upper Quinault River watershed and critical sockeye spawning habitat. There are many more examples in the region.

The state Salmon Recovery Funding Board just announced $43 million in grants for salmon habitat restoration projects across Washington. That’s a lot of money, but it’s a drop in the tub compared to the hundreds of millions we have already spent. If we don’t protect our investment, we have wasted every one of those dollars.

We lose value on our investment every time a local government allows a project to be overbuilt or a bulkhead constructed without keeping an eye on the impacts to salmon. Our efforts are undermined when we find out that in San Juan County alone permitted private docks were overbuilt by 52 feet on average.

Are we protecting the gains we have made in habitat? Or are we trying to fill a bathtub full of holes? We need a comprehensive, cooperative effort to find out. Tribal, federal and state governments, user groups and other stakeholders, all of us must work together to track salmon habitat and see how we are doing on our goals for protection and restoration.

A habitat monitoring program was written into the recovery plan for Puget Sound chinook, but it sits on a shelf. It’s time that it be put into action.

The salmon aren’t that strong. They need our help now. We know two things: the status quo must change and forward is the only direction we can go.

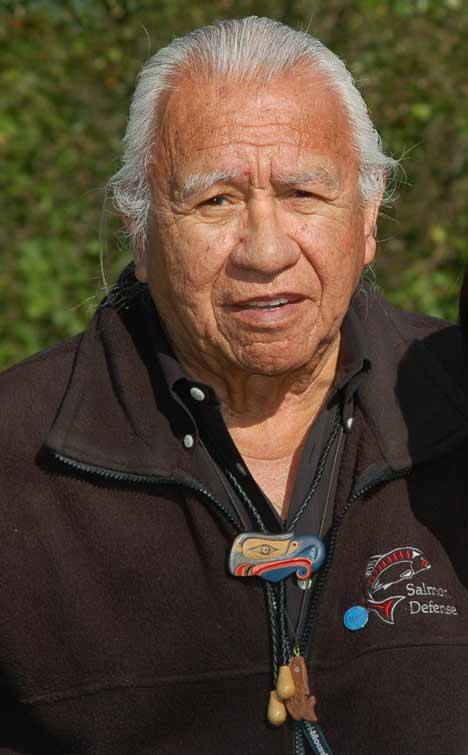

— Billy Frank Jr., Nisqually, is chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission. Members with ties to the San Juan Islands include the Lummi Indian Nation, Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, and the Tulalip Tribes.