By Mike Vouri, former National Park Superintendant.

The advent of fall weather has resulted in the classic rain shadow the past few days, best seen from American Camp. I photographed several views (offered here) looking south from the old county road trail and the redoubt to the Olympics Mountains, hiding beneath a cloud bank on the far side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

This land left the county tax rolls more than 50 years ago with the creation of San Juan Island National Historical Park. As veracity and imagination are under assault in some quarters this election season—which includes renewal of the San Juan County Conservation Land Bank, which conserves similarly spectacular forest and prairie lands—it may (or may not) be of some benefit to review a little history.

Should we have to pay to enjoy nature?

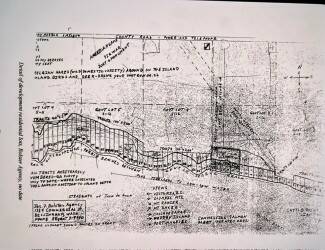

There was a drive in the early 1960s to develop the American Camp prairie and South Beach—then on the tax rolls—into high-end vacation housing. Plans called for 66 individual lots, extending like piano keys from the bluffs to the open prairies. They would be available in 100’ x 500’-foot and 100’ x 200’-foot parcels at $17 ($170 today) per frontage foot. What a bargain. Most of the property (about 282 acres), which included the former garrison site and prairie, belonged to the Seattle- and Bellevue-based T.J.R. Corporation. These would eventually abut 10 beachside properties (already sold) in the so-called American Camp Subdivision, located along South Beach.

The properties were still in the development stages when in June 1966 President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law Sen. Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson’s enabling legislation creating San Juan Island National Historical Park. The bill specified that the new national park was to commemorate the peaceful resolution of conflict through the interpretation of the San Juan Boundary Dispute, better known as the Pig War. Over the years the park has expanded that theme to preserve and protect the cultural and natural landscapes of American and English camps, as well as celebrate the island’s indigenous heritage.

Following condemnation proceedings, covering 548 acres, in Seattle, Bellevue and Friday Harbor, the federal government ended up paying the authorized $3.5 million for 1,752 acres for both park units.

The conservationist, Frances Troje*, whose husband at the time,Albert Troje, was listed as owner of T.J.R., presented me with a map and file of documents relating to the vacation development in June 1995. This was shortly after I arrived for duty as lead interpreter at San Juan Island National Historical Park. As of June 1965, T.J.R. was among 12 of 24 American Camp property owners identified as refusing to sell and slated for condemnation proceedings, according to the park’s administrative history. Additionally, Roche Harbor Resortheld another 80 acres at English Camp, which it also did not wish to sell.

Having spent vacation time in the old McRae house, now the Officers Quarters (HS-11), Troje told me she was never comfortable with the development proposal. And, as her years as a conservationist with the Mountaineers attest, she donated her share of the property—identified as “American Campsite,” which included the parade ground and BelleVue Sheep Farm sites—to create the park. This caused no end of friction among her husband’s partners in the development, she said.

The administrative history states: “In any condemnation situation, there are going to be ill feelings on behalf of those losing their property. San Juan Island was no exception, and the landowners in condemnation proceedings, most of who remained on the island, provided a source of anti-park sentiment on the island. This resentment has quieted as time has passed.”

This is due in large part to the work of the park’s first superintendent,Carl Stoddard, tasked with acquiring the properties and assembling the park infrastructure we know today. This included what was known in 1972 as the “American Camp Bypass Road,” that traverses the park to Cattle Point. It all required support from the community. This he achieved so remarkably that he retired to San Juan Island, where his wife Jane taught school for many years.

But has resentment over public lands really quieted?

Not from the tenor of the Land Bank opposition. Should they succeed, we need to ponder what becomes of these properties if opened to development in whatever form it may take. Will the prime real estate (which is what it will become) be farmed or short platted for “affordable” housing?

The national park staff here experienced considerable stress following the 1996 elections, when the Republican Party took control of the House of Representatives under the slogan, “Contract with America,” coined by incoming Speaker Newt Gingrich. An element of the“contract” was a bill (HR-260) to create a “Park Closure Commission.” San Juan Island National Historical Park was on a listthat primarily targeted national historical parks and parkways.

It was a long winter for us. But American citizens from both ends of the political spectrum reacted furiously to the legislation with thousands of letters and telegrams. Coupled with a grassroots campaign by the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA)and the exhortations of Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, the bill did not stand a chance and lost in a resounding floor vote.

“We can take down the ‘For Sale’ signs at our parks, as there will not be a commission that will close, privatize, or sell our parks to the highest bidder,” said Rep. Bill Richardson (D-NM), who led the fight.

There was a collective sigh of relief here. We felt reassured that,among all Americans, rare natural and cultural landscapes are sacrosanct and worthy of preservation.