Our five senses combine in another sense that is important to all of us as human beings: a sense of place. It is a powerful sense, it takes time to develop and can be lost when folks move around a lot from place to place and job to job.

I have been blessed with a strong sense of place for my home, the Nisqually River. I know my place, my home. It’s where I feel the best.

Place is an important part of treaty tribal fishing rights, too. Our rights are place-based.

That means we 20 treaty Indian tribes in western Washington can only fish in the places we have always fished. These are our “Usual and Accustomed” fishing places, the places where we exercise our treaty-reserved right to fish.

For my tribe, the Nisqually, that is an area in southern Puget Sound. For my friends in Neah Bay, the Makah, it is an area around Cape Flattery at the northwest tip of the Olympic Peninsula. I cannot go to Neah Bay and exercise my treaty-reserved right to fish as a Nisqually tribal member.

Good fishing or bad, we have our places. If the fishing is poor, it’s poor. We can’t pack up like sport fishermen and travel to where the fishing’s better. We have to work to make it better from right where we’re at.

The Puyallup Tribe of Indians has seen its fall chinook fishery shrink to almost nothing in the last few years. Because the wild chinook run returning to the Puyallup is so small, all fisheries must be constrained to protect the weak wild run. This means that even though thousands of hatchery chinook are available to fishermen throughout Puget Sound, the Puyallup Tribe has less than one day of fishing to protect wild salmon in their home river.

Our place-based fishing rights require most of our tribes to fish in what are called terminal areas. These are places like bays and lower rivers where salmon gather before heading upstream to spawn. They are the places we have always fished, and will always fish.

Place limits on our treaty rights mean we have to do an extra good job of managing our fisheries. We have to ensure that we focus harvest on strong hatchery stocks while we work to protect and recover weak wild stocks. We have to work to fix the habitat in our watersheds. We have to work hard at management to make sure fish come back to us and that enough survive to spawn and continue the run. We have to watch our fisheries closely and adjust them as necessary to make sure we aren’t having too great of an impact on the run.

Time, place and method are the main ways that we control our fisheries. We limit our fishermen to a certain number of days of fishing and then monitor those fisheries closely to see if we need to make any changes. Treaty tribal fishermen are allowed to fish only in their tribe’s “Usual and Accustomed” fishing areas, and sometimes are allowed to fish only in certain parts of those areas. We also regulate fishing methods, such as net mesh sizes and lengths to be more selective in our harvest.

By the time the salmon reach these terminal areas, weak and strong stocks have sorted themselves out. We know where, when and how many fish we can selectively harvest without harming the run.

The next time you see one of us tribal fishermen exercising our treaty right in a bay or at a river’s mouth, remember why we are there. We are there because that is where we must be to exercise our treaty rights.

We have a good sense of place. It’s right here on every major watershed in this region as co-managers of the salmon resource.

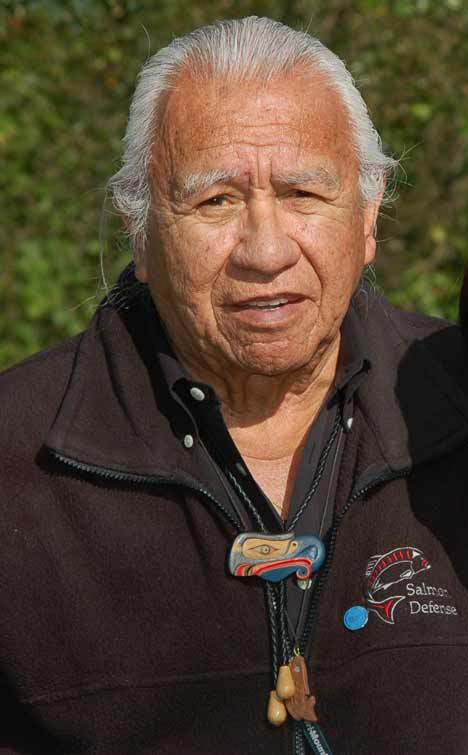

— Billy Frank Jr., Nisqually, is chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission. Commission members with ties to the San Juan Islands include the Lummi Indian Nation, Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, and the Tulalip Tribes.