‘Important link in ocean food chain’

By Susan Key

Special to The Journal

“Found off Iceberg Point, Lopez Island” is the enigmatic label on a specimen of reef-building glass sponge unearthed at the U.W. Friday Harbor Labs in response to a querry by Professor Paul Johnson.

Why the interest? “These deeper water sponge reefs create habitat and act as nurseries, especially for rockfish,” Johnson said.

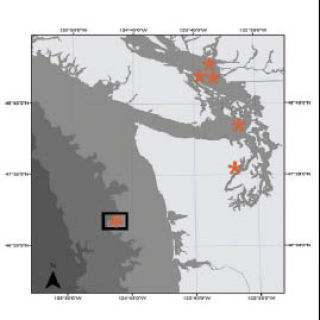

Thought to have gone extinct, glass sponge reefs were rediscovered in Georgia and Hecate Straits during the 1990s. Johnson, an oceanographer at the University of Washington and chief scientist on 38 deep-water cruises, has spent most of his career working on hydrothermal systems on the Juan de Fuca Ridge and became involved “obliquely.”

Dr. Ken Sebens, director of the U.W. Friday Harbor Labs and a member of the county Marine Resources Committee, said the Labs is aware that the sponge reefs are off Iceberg Point but other locations in the San Juans are not known because there hasn’t been any funding to map them.

Johnson accompanied Verena Tunnicliff, University of Victoria, on a 2005 cruise to look at the impact of oil-exploration seismic work on the Fraser River glass sponge reef. He was so impressed by the rich environment of these reefs that he started looking for them in Washington waters.

His June 2007 cruise to the margin off Grays Harbor found stunning mounds of creamy white and golden yellow glass sponges, with accompanying great numbers of fish, crustaceans and zooplanktons.

Emily Marshall, in the winter 2008 issue of Northwest Science & Technology, quotes Johnson as saying that “in an otherwise sparsely populated area of ocean, glass sponge reefs housing zooplankton, sardines, crabs, prawns and rockfish stand out as an important link in the ocean food chain …”

“Similar to their coral reef cousins, the sponge reefs provide protection for pregnant and young fish, as well as refuge for many other species.”

The Grays Harbor reefs are massive, hundreds of feet in length and rising 6 to 15 feet off the floor. Dating procedures indicate that they are thousands of years old, but sonar scans show that one pass by a bottom trawler can end in destruction.

Glass sponges need silica-rich waters to build their exoskeletons, and a hard substrate, either rock or old reef, upon which to attach. Some 150 million years ago, the evolution of more efficient silica scavengers — diatoms — likely forced glass sponges into deeper waters. Today, silica and oxygen levels are high enough for glass sponge survival at depths around 650 feet, where light levels are too low for their diatomaceous competitors.

Water temperature is important, and ideal conditions are found in coastal waters from Oregon around the Aleutians to Siberia, and along the edge of the Antarctic ice sheets.

Locally, rivers emptying into the Salish Sea provide silica but a hard bottom is difficult to find. Bathymetry off the south side of Lopez Island indicates a long horizontal hump, most likely a remnant glacial moraine, considered perfect habitat for a glass sponge reef.

Oases of glass sponge reefs are just one more example of the incredible biological diversity in the San Juans. Fourteen years ago, a grassroots effort to gain local control over our shared marine resources resulted in the county’s Marine Resources Committee.

In July 2007, recognizing the importance of healthy marine resources to the island economies, the San Juan County Council approved the Marine Stewardship Area Plan for all of San Juan County.

Johnson gave a presentation, “Glass Sponge Reefs in the Pacific Northwest,” on May 7 as the kickoff to the San Juan Nature Institute’s Spring Orcas Island Lecture Series.

— Susan Key is executive director of the San Juan Nature Institute