Still dressed in his uniform and hours off the plane from Vietnam, veteran Peter DeLorenzi was unable to cash a check in order to buy a bus ticket home because he no longer resembled the man depicted on his photo identification.

“Coming home was rough,” he said.

De Lorenzi is not the only Vietnam soldier who had difficulties reacclimating. In fact, according to DeLorenzi, more have died by suicide after returning home from that war, than died in it. Combat photographer Donald Cordi is one of those veterans who committed suicide.

Cordi served in one of the units that saw some of the heaviest combat, according to DeLorenzi. At the age of 23, shortly after setting foot back in the United States, Cordi, like so many others, died by his own hand.

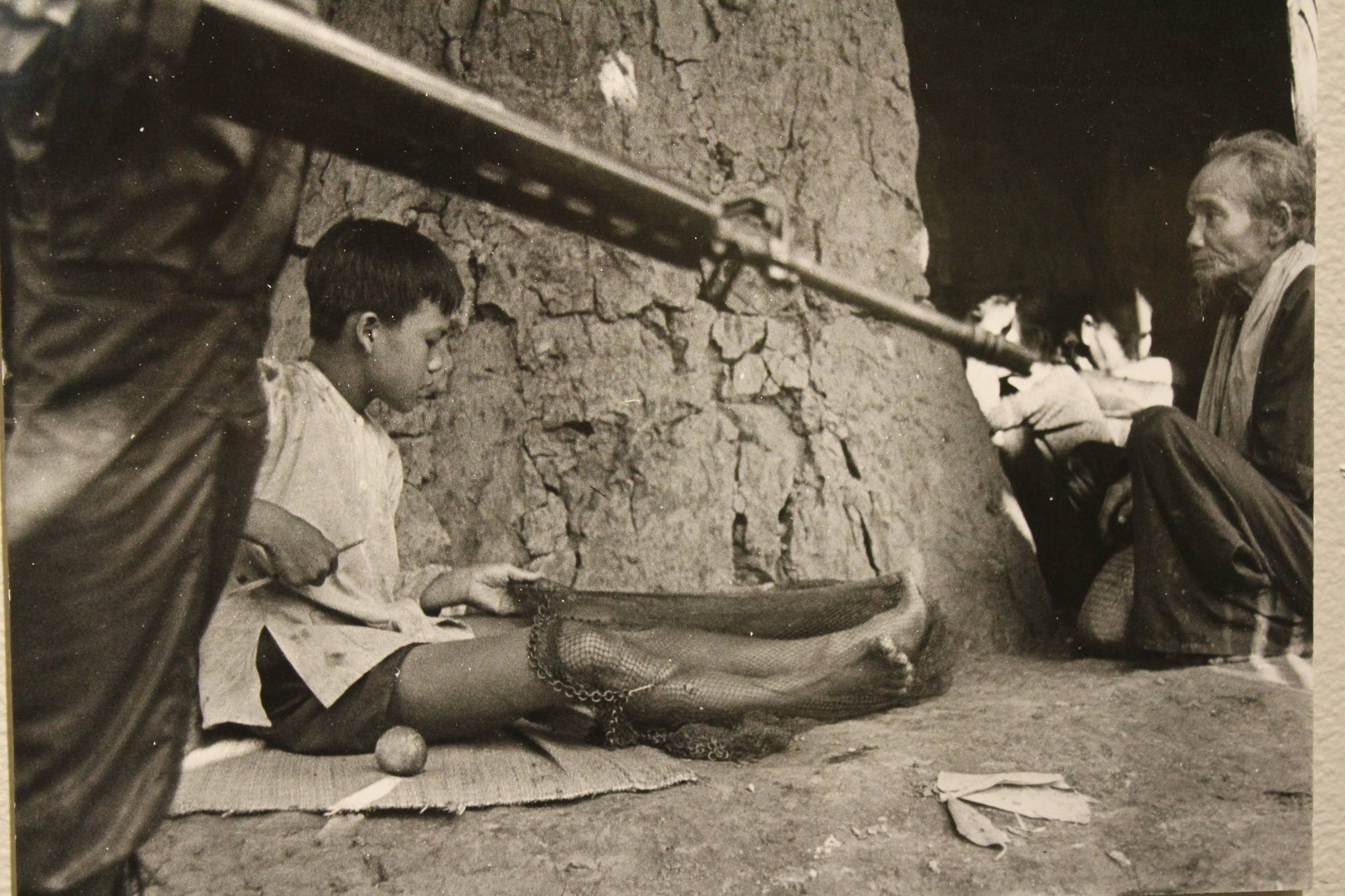

Cordi’s photographs live on, however, and are part of the San Juan Islands Art Museum’s exhibit “MY WAR: Wartime Photographs by Vietnam Veterans,” opening April 5 through June 3. This is the first showing of My War on the West Coast, having previously been shown in Highground Veterans Memorial Park in Neillsville, Wisconsin, in August 2016.

The collection features photographs, poems and other items from Vietnam veterans that captured their lives and memories of the war. DeLorenzi worked to collect additional items from local veterans, as the “A War Never Ends” exhibit which includes Cordi’s photograph. The United States military veterans are admitted free, tickets for adults are $10 and ages 18 and under are free. Mondays are “Pay As You Can Days.” Sponsors include Dave and Nancy Honeywell Charitable Fund, Gary and Susan Sterner, Printonyx and Harbor Rentals.

Thousands of miles away in the thick of the jungle, fighting for their lives and country, soldiers in Vietnam had no idea what was happening back home in the U.S., according to DeLorenzi. Shell shocked from war, still uniformed but no access to money and forced to hitchhike 7 miles to his mother’s house, he said, people threw bottles at him, yelled profanities at him, pretended to stop and give him a ride, only to drive away the moment he got close to the car. In time, he learned how unpopular the conflict was, and understood people were taking their anger and resentment out on the veterans. As a result, these soldiers did not acknowledge they had ever served, even to those closest to them.

“No one wanted to admit to having fought in that war,” he said. His own wife did not know he served in Vietnam until five years after they were divorced.

Not talking about the violence they witnessed became a survival mechanism for these veterans.

According to the museum’s description of the exhibit, “much of the material was previously kept hidden away, even from family and friends. Many veterans destroyed their photographs … in order to purge painful memories and close a visceral door to the past.”

Cordi and DeLorenzi shared a passion for photography as well as being veterans of the same war.

“Cordi is my hero,” DeLorenzi said. “I feel like he is my brother.”

Cordi’s aged yellow Kodac box of war photographs came into DeLorenzi’s possession three years ago, after a fellow veteran who worked at the San Juan County Transfer Station found it among the garbage. Three years later, after the SJIMA approached him to assist with contacting veterans and collecting material for the exhibit, DeLorenzi began avidly searching for information about the mysterious photographer— who at that time was only known because of a name on the photographs.

Through a friend, DeLorenzi found an old Oregon newspaper clipping with Cordi’s obituary. The puzzle’s trail led him to the Willamette National Cemetery, Portland, Oregon, where Cordi is buried near his parents. DeLorenzi has not been able to contact any other friends or extended family but hopes someone out there will be able to provide him with more details about the man behind the camera, and how the container of photos came to be on San Juan Island.

“As far as we can tell, he had no ties here, so it’s an absolute mystery how his photos ended up here,” DeLorenzi said.

Judging from the photographs, Cordi served in a unit that was on the front lines of the action, De Lorenzi said. He added that many of the pictures contain emotionally heavy, graphic subject matter. From Cordi’s young age, DeLorenzi guessed that he signed up straight after high school, meaning the photographer saw a lot of the war by the time he was 20.

“His unit had close contact with the Viet Cong and saw a lot of casualties,” DeLorenzi said. “When you’re in your teens [and] early twenties, that stays with you.”

Since some of the photographs had been printed and assembled for framing, DeLorenzi said he believes Cordi wanted them to be shown in an exhibit someday. Fifty years later, the photos are, in “The Cordi Collection.” DeLorenzi hopes the collection will continue on with the rest of the “MY WAR” exhibit as it tours across the nation.

“He needs to be with this show,” DeLorenzi said.

DeLorenzi added that not only will viewers see veterans’ memories of the war, but will catch a glimpse of their post-Vietnam life, the various ways many of them became involved in and support their community.

“It was a long journey, but I think today, we are all proud to have served,” he said.

For more information about this or other upcoming exhibits, visit sjima.org.