Islanders may remember James Longley from his childhood days. He graduated from Friday Harbor High School in 1990. From there he has gone on to create critically acclaimed documentaries. Longley is currently in Afghanistan but has brought his art home with the latest exhibit “Looking into Kabul” showing at the San Juan Islands Museum of Art through September 12.

“I came to Afghanistan at a time when people were starting to tune it out as a subject of conversation, in late 2011,” Longley said. “We were starting to tune it out because we must have realized by then that we were going to lose the Afghanistan war and that there was no good outcome.”

He began making documentaries in the Middle East over a decade earlier, in the Gaza Strip. The experience of living and working there impressed upon Longley, he explained, how many crucial things are occurring globally that Americans should know more about.

“The 9-11 attacks happened while I was editing my Gaza Strip documentary in Brooklyn. By the time I was free to make a new film, the U.S. had already occupied Afghanistan and was about to invade Iraq. I chose to make my next two documentaries about Iraq, and they were critically successful enough to allow me to continue,” Longley said. “After Iraq, I tried unsuccessfully in Iran and then Pakistan for several years to make feature documentaries – beautiful countries, but difficult to work in. Finally, in Afghanistan, I was able to realize my idea for a school-set documentary that is really a big-picture movie about the broader Afghan situation. That film is called Angels Are Made Of Light.”

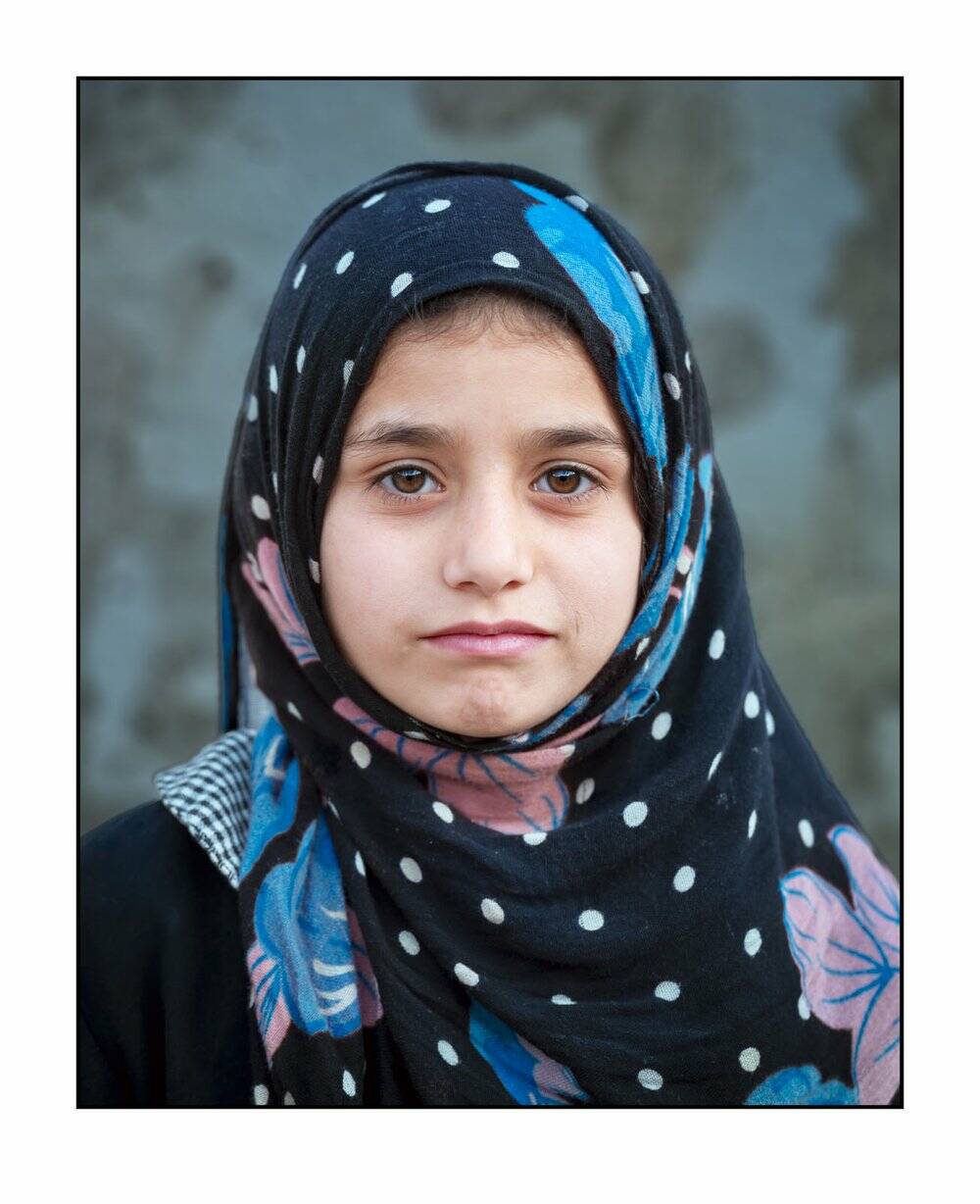

“Looking Into Kabul,” follows both students and teachers at a school in Kabul, in a neighborhood that is slowly rebuilding from past conflicts. Through his portraits, Longley interweaves the modern history of Afghanistan’s present-day offering an intimate and nuanced vision of a society living in the shadow of war.

Longley explained in the SJIMA press release, “We cannot understand Afghanistan in its physical reality and human complexity because most of us will never go there – most of us probably *should* never go there. At the same time, we are missing the kind of mediated, virtual experiences… I believe this is a real problem. Not an Afghan problem. An American problem. A problem with how we fail to see a place, to develop an understanding for a people even two decades after having invaded and occupied them with our massive boondoggle military. It is a problem of both the Left and the Right, the rich and the poor.”

There are a number of similarities between the two cultures, partially simply because there are many Afghans living in the states.

“On one side, there’s no way to make a clear distinction between our cultures as hundreds of thousands of Afghans live in the United States; the threads of Afghan culture are also part of the American fabric,” Longley said.

“The most important thing in Afghanistan is family – usually meaning the extended family. Americans like to say that family is important, but the importance of family far outweighs the importance of the individual in Afghanistan, which is generally not true in American culture.”

In Afghan culture, Longley continued, there is something like ritual politeness. In Iran, this politeness is called “taarof.” Taarof means that communication is much less direct and more complicated, and a number of social codes are different from what Americans may be used to. “Also – to be fair – Afghanistan comprises many different cultures, tribes, and language groups; we can’t really talk about Afghan culture as a monolith,” He said.

What did surprise him was the gender divide. “The gender separation in Afghanistan is more stark than in any other country to which I’ve been. It was like that under the NATO-backed government when I was there from 2011-2015, and it’s like that today under the Taliban – just more,” Longley said. “This is particularly true outside of the big cities. Driving through mountain villages, women working in the fields turn their faces away from the car as it passes.” He added that he has lived under the Taliban for six months now and has not had a conversation with an Afghan woman during that time, with the exception of briefly meeting women teachers who were included in his last film.

When asked why the Taliban has been so difficult to fight, Longley said, “Not to overuse a line, but we have the watches; they have the time.”

Longley continued, explaining that what he meant is that to understand the Taliban’s sticking power, it’s useful to explore all those things about the Taliban that the American public was not being told during the war. In many communities, for example, located not even an hour’s drive outside Kabul, Longley said “the Taliban were often local boys, viewed as heroic freedom fighters, bravely laying down their lives to fight against the tyranny of constant CIA night raids and drone strikes. The Taliban played Afghan politics correctly, on their home turf, while we played God from video game consoles thousands of miles away. By the end, village children all over the country saw us as vandals and villans.”

As long as America actually fought the Taliban, rather than addressed the issues that made the Taliban popular in areas under their control, Americans were always going to lose, Longley said. “The American military and the CIA special forces are simply not able to conduct politics in an environment like Afghanistan, and yet they were often the sole instruments of our policy.”

When asked if there are hard feelings toward the United States, Longley responded, “Nobody likes the way in which the US left Afghanistan. The planning and conduct of the withdrawal just seemed disorganized and irresponsible. On the ground, it was barely managed chaos. It could have happened very differently.”

Longley pointed out that US economic sanctions against Afghanistan hurt the most disadvantaged. In the end, he said, most people’s views of the U.S. are tied to whether they benefited from the US occupation, or whether they were terrorized by it.

As to whether negative attitudes impact his work as an artist, Longley replied, “sometimes, in a mountain village, I might encounter a man who witnessed his son being killed by a CIA drone strike. In this kind of case, much diplomacy is required.”

America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan left many struggling. There are many ways to assist those in need, according to Longley. Thousands of Afghan families eligible to come to the United States via the Special Immigrant Visa program are still stuck in Afghanistan and third countries. “These are former US Army translators and others, many of whom worked directly with U.S. forces for years, making their prospects in the new Afghanistan quite bleak,” he said. “The SIV program is overwhelmed and appears to be a low priority for the Biden administration. There are plenty of Afghan people stuck in bureaucratic limbo who could use a hand understanding paperwork or someone to advocate for them with their local representatives.”

To learn more, and to help SIV applicants, visit https://www.evacuateourallies.org/advocacy.

Food insecurity is also an issue. “Many of the nearly 40 million people remaining in Afghanistan now face food scarcity and famine,” Longley said. “When the United States withdrew our military and ceded Afghanistan to the Taliban in August 2021, we decided to continue an economic war against Afghanistan in the form of frozen foreign currency reserves, lack of access to international banking and credit, and many other forms of sanction. These sanctions first impact the most vulnerable – children and women – while solidifying Taliban power over a dependent population,” he explained. Human Rights Watch has written a report on the impact of economic policy toward Afghanistan here: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/03/01/afghanistan-economic-roots-humanitarian-crisis.

According to Longley, one specific reliable local Afghanistan organization that has been helping provide direct food aid to people in Afghanistan is Aseel. to learn more about them visit https:/aseelapp.com.

“I have witnessed their effectiveness firsthand, and routed food aid through them in the past to benefit the teachers who are featured in my documentary film, Angels Are Made Of Light,” Longley said.

He encouraged his hometown residents to reach out with any questions, or just say hello at jameslongley.com.

To see the exhibit, SJIMA hours are Thursday through Monday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tickets for adults are $10 and children 18 years and younger are free. Members of the museum are free.