As the island begins to settle into spring with longer days and more sunshine, this time of year marks the arrival of fox kits, which are primarily born in late March and early April. With their small, fuzzy bodies and bright blue eyes – turning amber as they reach one month – they are an exciting sight to behold. Many photographers have come to the island to capture the foxes’ beauty, particularly following the circulation of a video shot by wilderness photographer Kevin Ebi in 2018 of an eagle and a fox battling over a rabbit mid-air, (see https://www.sanjuanjournal.com/life/bald-eagle-and-fox-battle-midair-on-san-juan-island-photos/) Since then, there has been an uptick of reports and incidences of aspiring photographers getting too close for comfort with the foxes, invoking confrontation from island residents aiming to protect the animals. The Journal met with Jeff Hodge, Lead Interpretive Ranger for the San Juan Island National Historical Park, to learn more about the issue.

Hodge has worked for the Park for the last seven years, and as an interpretive ranger, he is a “storyteller” for the park, focusing on everything from history and geology to the flora and fauna of the park, as well as climate change and everything in between. Hodge explained that in 2018, the island saw the first major uptake of conflict between photographers and islanders, occurring mostly around the cape and on the property of the Washington Department of Natural Resources and the Bureau of Land Management. Although there have been incidents of misunderstanding between islanders and visitors approaching wildlife in the Park, Hodge is grateful there have not been instances of high tension and confrontation.

“We hear about [cape incidents] through Facebook and Instagram so we’re in the loop because of that, and we do get reports from visitors who have been down there,” said Hodges. “Lots of people are thankful that it’s not happening in the Park. We’re thankful for it too; there’s nothing worse than confrontation.”

According to Hodge, fox kits are especially vulnerable when it comes to contact with people, as they have yet to be trained by their mothers to keep their distance. Coming in closer contact with humans can draw them closer to roads and cars, putting them in greater danger.

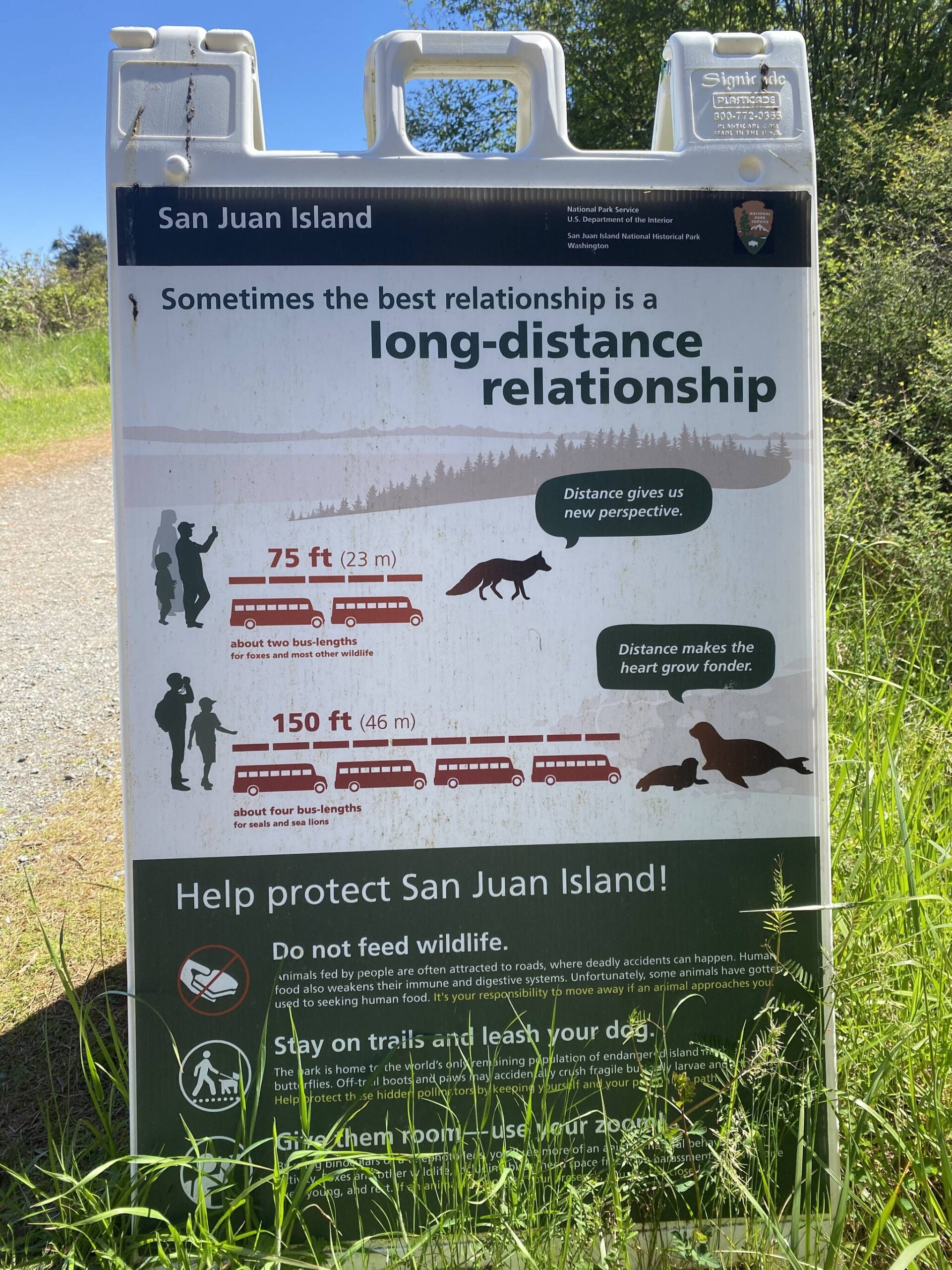

The Park’s response to the rising number of incidents over the last few years has been to de-escalate heightened tension by taking a step back from head-to-head conflicts and instead increasing protective measures such as implementing better signage and building higher fences in the prairie. In fact, the primary reason for protecting these fenced-in areas is because it is habitat for Island Marble Butterflies. According to Hodge, there are roughly only 500 of the butterflies left, and their habitat in the Historic Park is likely their final resting ground. The Park staff put up the fencing and improved signage last year, and Hodge remarked that the Park has already experienced less instances of visitors getting too close to wildlife.

“We take action when it’s needed, but we don’t enforce animal contact laws. We educate and advise,” said Hodge. “We don’t have the enforcement authority to be able to intervene in an enforcement capacity so we rely on visitors to do the right thing and islanders to help us monitor. Our tactic is education.”

When it comes to wildlife, specifically foxes, the guideline that Hodge and the other rangers and Park staff use is to keep a distance of 75 feet, roughly the length of three school buses. Of course, visitors cannot control what the animals do, so it is the responsibility of the visitor to maintain that distance. Additionally, Hodge emphasized the importance of not feeding the animals as well, as this can make animals reliant on humans for food, deterring their survival skills and drawing them closer to contact with human environments like roads.

As for islanders who witness someone getting too close to wildlife, Hodge expressed that islanders should not put themselves at risk by confronting the offender and trying to enforce Park policy. Rather, being the eyes and ears of the Park and reporting issues to the rangers is extremely helpful, as Park services are short-staffed and have to manage over 2,000 acres on the island.

“We can’t be everywhere at once, so having that extra set of eyes from islanders and visitors is incredibly valuable to us,” said Hodge. “This is a long-term effort by the Park to protect habitat and deconflict between human beings and animals the best that we can, so it’s in our best interest to recruit the public and make them aware of what those rules are, and then without asking them to intervene, giving us the information that allows us to intervene in some way.”