Submitted by Kwiaht

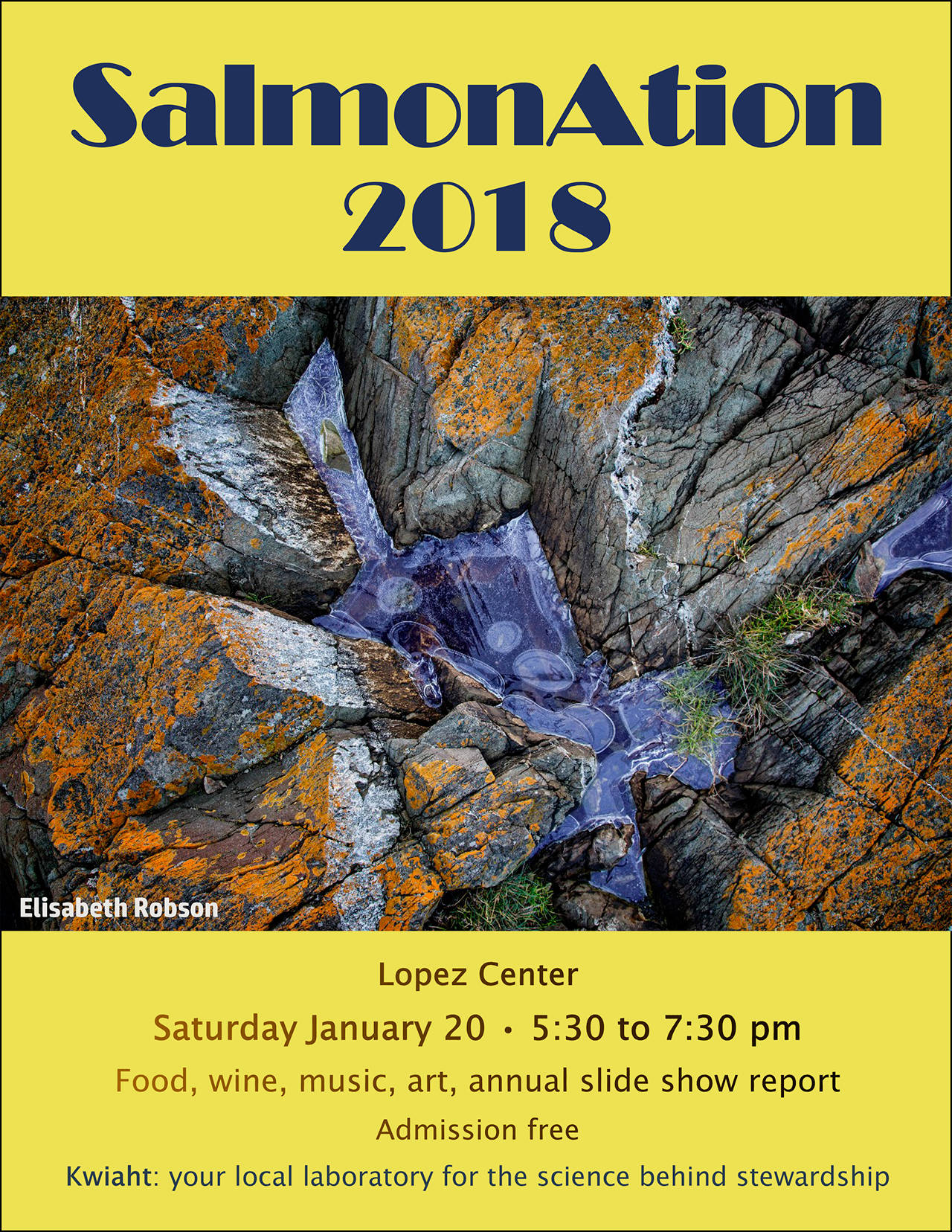

Kwiaht celebrates a decade of community science and a significant expansion of its fishery research program at this year’s SalmonAtion event at Lopez Center, on Saturday, Jan. 20 from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. As always there will be a light buffet, a choice of Lopez Island Vineyards wines, entertainment, and a slideshow reviewing highlights of this past year’s research. Photographer Elisabeth Robson is this year’s featured artist and her work will be on display. Admission is free.

There are westbound ferry connections so that folks can come from Orcas or Friday Harbor and still get home hat night.

“Our work on marine food webs has reached a turning point,” Kwiaht director Russel Barsh said. “For years we worked outside of the mainstream of salmon and killer-whale research, to a great extent fueled only by volunteers, local donations, and enthusiasm. We gradually won the respect of the scientific community, and we begin 2018 with a regional network of partnerships and funding to last us several years.”

The lesson here, Barsh added, is that “people can do science in their backyards”.

Barsh was first to challenge the conclusion of state and federal agencies in 2001 that the San Juan Islands provide no habitat for endangered Puget Sound salmon stocks. He hypothesized that the islands provide a way-station or “lunch stop” for outbound juvenile salmon and inbound adults that contribute to their growth, survival, or fecundity. He also drew attention to the role that resident sub-adult Chinook salmon (or “Blackmouth”) might play in the ecology of Southern resident killer whales. The first annual SalmonAtion event at Lopez Center in 2009 presented two years of beach-seine data suggesting that juvenile Chinook feast on the islands’ herring and sand lance as they make their way seaward, inspiring Kate Scott’s fishy “all you can eat buffet” print — the original of which still hangs on the wall at Kwiaht’s office in Lopez Village.

A major two-year state-funded study released last month involving a dozen state, federal and Tribal agencies as well as Kwiaht, sampling Puget Sound Chinook along their migration paths from Puget Sound rivers and estuaries to the San Juan Islands, found that their diet shifted from invertebrates such as larval crabs and insects to fish — almost entirely herring and sand lance — when they reach the islands. This shift in diet was accompanied by more rapid growth, confirming the crucial role of the San Juan Islands in the early life history and survival of Chinook.

“We continue to learn more about salmon in the islands’ ecosystem from annual seining at Watmough Bight and Cowlitz Bay,” Barsh said. “Above all we are beginning to see evidence of a decadal cycle in Chinook abundance that corresponds with the Pacific Decadal Oscillation in ocean climate, and also seems linked to climate-driven cycles of herring and sand lance.”

The focus of Kwiaht research is moving towards understanding the way the PDO affects forage fish, including studies of cycles in the abundance of the plankton that forage fish eat, and changes in parasites and disease transmission that may be temperature-related.

Two new projects get underway this month. One project aims to better understand the diet, health,and reproductive biology of Pacific sand lance, which appear to make up about half of what juvenile Chinook eat when they migrate through the islands, as well as much of the diet of tufted puffins, rhinoceros auklets and marbled murrelets. It was generally believed that these small fish ate copepods (tiny crustaceans), and spawned on beaches in early winter. Kwiaht pilot research in 2016-17 found that sand lance enjoy a wider, more flexible diet that includes other larval animals and that they spawn in spring and summer as well, perhaps offshore.

Another data gap that Kwiaht will begin to address this year is the ecology of Blackmouth salmon: what they eat all winter, whether they remain in the islands’ waters continuously or take trips to the Strait or the ocean, how long they take to mature, and what factors determine their survival and abundance. For this study, Kwiaht is counting on local anglers to collect gut contents and tissue samples from their winter catch, rather than conducting a separate research fishery.

“We don’t want to take any Blackmouth off folks’ dinner plates,” Barsh explained. Sampling kits and instructions will be available at the January 20 event at Lopez Center, together with more details on what can be learned from liver flukes, otoliths, blood, scales, and other specimens taken from local anglers’ “keepers.” Lab work will mainly be carried out at Kwiaht’s expanded facility at Lopez school, with help of students.

Interlocking partnerships with a growing network of scientists on the mainland make this all possible. Laboratory analyses of Blackmouth will be split with the state’s wildlife laboratory in Olympia, and NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle. Zooplankton and parasites will be identified at the University of Washington by professors Julie Keister and Chelsea Wood and their students. Sand lance specimens caught by Kwiaht in the islands will be compared with specimens contributed by scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey, NOAA, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and Treaty Tribes. Long Live the Kings, the only other nonprofit involved thus far, has been instrumental in securing funding and providing coordination.

“Chinook salmon remain at historic low,” Barsh said, “but now we are focused on better questions, and have a lot more talent and technical resources to tackle those questions. Kwiaht and the Lopez community helped re-define the problem and make it all happen.”

Kwiaht volunteers fish Watmough Bight from May to September and welcome visitors to help pull the nets and sort fish. Email info@kwiaht.org for more information and schedules.