White blooming currants can be found throughout the islands, dispersed by Eugene Kozloff, and his colleague Richard Norris. They gave currants away by the armloads, according to Fiona Norris, science director at the San Juan Island Nature institute.

“He really encouraged people to plant native species,” said Billie Swalla, director of the UW Marine Labs, adding that Kozloff was very involved in the Nature Institute and Master Gardeners.

While botanist and biologist Eugene Kozloff has passed away his blooming currants live on and with them the memories of his life. Kozloff who had taught and researched at the Labs since 1966, passed away March 4 at the age of 96. He leaves behind a trail of plants, books he published on flora and fauna of the islands and pacific northwest, as well as footprints on the lives of students and scientists during the years he taught and researched at the Labs.

Swalla herself recounts her first Kozloff encounter. Swalla visited the Labs in 1998, in search of hemichordate, a type of marine worm she was researching. No one at the labs knew where on the island she might find any, they kept telling her “ask Koz” and directed her to his lab.

In his lab, Swalla introduced herself to Kozloff, and asked if he knew where she might find these unique worms.

He looked down at her high heels, her skirt – she was not dressed in field gear. “They live in the mud you know,” he finally said.

“I know,” said Swalla.

“And they stink too,” He added.

Swalla nodded, and he proceeded to tell her she would have to go back to Anacortes, and north to Padilla Bay. Swalla found her worms right where he said she would and finished her paper. She gave Kozloff the paper, which he did read, Swalla knew because he complimented her on it later. Thus a friendship was born. Her story is one of many examples of his encouragement to both students and fellow scientists.

According to Richard Strathmann, another colleague, Kozloff often took the time to help scientists publish their work in English when their written skills were limited, which as English is now the international language of science, can be an obstacle for many good scientists.

Being the son of a Russian Cossack, he spoke Russian, as well as some French and German. French came in useful when he worked in marine labs in Roscoff France, and later in Tunisia. However, it was with writing that Kozloff helped non-native English speaking scientist.

Foreign graduate students receive help from dissertation advisers, but later, as scientists, they rely on colleagues, who according to Strathmann, are often pressed for time.

“Kozloff was very generous in giving that time,” Strathmann said.

Kozloff began his interest in the sciences as a young child, always playing outside, once bringing a pet snake home, his daughter Rae Kozloff said. He kept it in some sort of cage. However, issues occurred when the snake had babies that slithered from the cage, down the stairs, and all over the house. Kozloff’s mother freaked out, Kozloff got in trouble, and they spent days rounding up baby snakes.

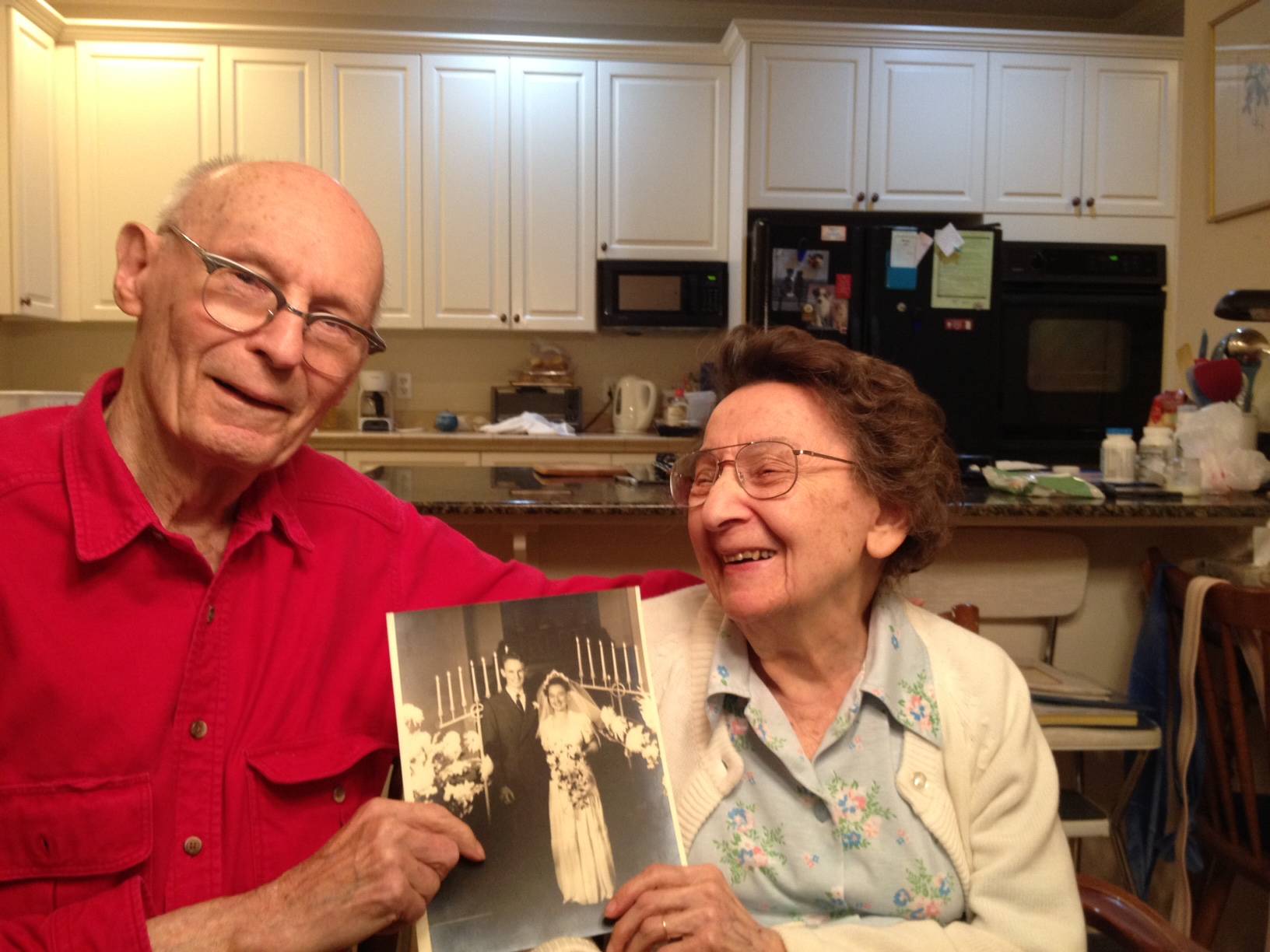

In 1944 he married Anne Solomon, and stayed together for an outstanding 72 years. Their daughter Rae explained their relationship, “A sense of humor and mutual respect, support and shared values. My father was the dominant personality, but he always listened to my mom and included her in all important decisions. She had her own strengths, just quieter.”

Kozloff’s books, “Seashore life of the Pacific Northwest Marine Invertebrates” and “Plant’s and Animals of the Pacific Northwest” among his others, have become staples in many science libraries. Strathmann noted when he first began teaching he would read a chapter in Kozloff’s seashore book on the habitat for that day.

“Part of Gene’s genius was knowing just which animals and seaweeds a new student would notice and ask about,” Strathmann said. “It made the introduction to the seashore manageable and enjoyable.”

Kozloff and Norris began what is known as the Zobot class. This popular class connecting botany and zoology, hence zobot, is still offered at the Labs, taught be Megan Dethier.

As professors are often rotated through the University of Washington’s main campus in Seattle, Kozloff, according to Laura Norris, owner of Griffin Bay Books and daughter of Richard Norris, took his turn teaching in Seattle as well.

“He loved candy,” Norris said, “if a student fell asleep in his class, which inevitably does happen, without missing a beat during his lecture, he would take out a candy bar, place it on the student’s desk, saying ‘here, maybe this will help keep you awake,’”

He was very respectful of his students, however, according to Swalla.

As far as discipline he would say about a troubled pupil was that they were a part-time student, implying they were not fully invested in their education.

Science was not Kozloff’s only forte. Kozloff loved opera and picked up some Italian as a result, and classical music. He played the Viola Da Gamba, a cousin of the Cello, and frequently entertained with fellow musicians. According to Rae Kozloff, her mother would play the piano, while friends would join in with flutes, violins and other instruments.

It was bringing science to the layman that Kozloff is most known for, however. Local naturalists and wildlife enthusiasts will continue to use his books as they navigate island’s plants and animals for generations to come.

“Kozloff was a wonderful guy, and cannot be replaced,” said Dennis Willows, former director of the Labs. “He had an encyclopedic memory that helped many of us figure out useful and interesting things about the creatures we ran across in the course of our studies.”