Editor’s note: As the nation grapples with an economic recession, 88-year-old Andy Hansen looks back on his childhood in Friday Harbor during the Depression of the 1930s. He remembers most islanders as resilient — especially the farmers, who had always learned to live independently from the “economic system.”

By Andy Hansen

Special to The Journal

Our current recession, with 10 million people unemployed, has brought back childhood memories to me of the Great Depression during the 1930s. I was a kid in grade school in Friday Harbor during this time.

The national unemployment rate hovered around 23 percent for several years. It fell off for a while, but by 1938 the rate was back up again.

In the San Juan Islands, there were many people out of work. The Works Projects Administration (WPA), initiated by Franklin D. Roosevelt, allotted money to the county for road maintenance. I remember, however, that some of the local farmers joked about the 10-member crew of WPA men that did road work for several years.

The farmers’ story was that any time someone happened to pass by the maintenance crew along the roads, the smallest man was always the one working while the larger nine stood around idly watching. Moreover, the small man doing all of the road work was a recent immigrant from Germany. The WPA program didn’t gain much respect from the local farmers.

My father, a carpenter and laborer, was often idle during the Depression. The standard working hours for a manual laborer was 10 hours a day, six days a week, with Sunday as the day of rest. The 40-hour week was started during the Truman presidency around 1950. In the winter, my father had a job at the pea cannery, opening cans of peas for routine quality checks. Since the peas from the opened cans were discarded, he would take some of them home for lunch or dinner.

My mother had always bought the cheaper cuts of meat from the local butcher shop, and continued to do so during the Depression. We frequently ate fried liver, tongue and heart. My mother also baked her own potato bread. Some of the time my father traded carpenter work with a store keeper for groceries.

The Great Depression played out differently for the farmers on Friday Harbor. Out on my grandparents’ farm, located off Farms Road, daily routine continued as usual. Their work was cyclical in nature and determined by the sun and the rotation of the earth.

As the sun rose and set, farmers and chickens followed in their cooperative life cycles without interruption — and seemingly independent of the Depression. In contrast, many others, such as those living in town, such as my parents, depended upon seasonal work in the canneries and scarce odd jobs to survive.

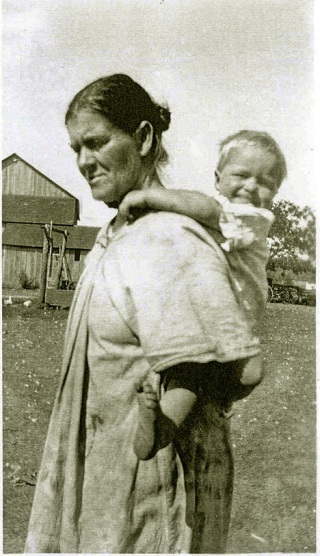

Farmers, especially those on the larger dairy farms, survived more easily during this period because they had always lived so independently. During the winter months, my grandfather and uncle rose in the dark to round up the cows — about 10 — for milking. They completed other chores, such as feeding six workhorses with hay and oats and cleaning out the stables — all before breakfast.

In the summer, during my high school years when school was out, I normally helped my Uncle Gordon Buchanan with maintenance work, such as cutting firewood for the winter, fixing fences, and gathering loose rock that had risen to the surface of the fields during cultivation.

During the Depression, the value of land took on a new meaning: Anyone in possession of even a few acres could plant gardens, maybe have chickens or pigs and sheep and perhaps a cow. Also those with timber owned a valuable asset both for firewood and lumber. My uncle George and Aunt Mary Wilson had 400 acres of timber they were harvesting and selling. So timber was a major asset.

My grandmother’s activities included fixing breakfast, feeding chickens, geese, ducks and pigs, gathering eggs, and washing the separator, which was used to separate cream from milk. The 10 or 20 gallons of skim milk left over — identical to the non-fat milk we pay over $5 a gallon for today — I usually carried in five-gallon pails over to a wooden trough for the pigs. The cream saved was put into five-gallon containers and taken to the creamery cooperative located in Friday Harbor on Spring Street, only a couple of blocks away from the outskirts of town.

About 5 o’clock in the afternoon, the same procedure was repeated as the cows were rounded up and milked again. The routine was followed seven days a week, year-round since animals never took the day off like humans do. At night my grandfather always went to bed early, before dark, just like the chickens and the other domesticated animals.

Farmers, and especially dairy farmers like my grandparents, were well supplied with food during the Great Depression. In the springtime, a garden about the size of two or three city lots was planted with potatoes, onions, and other vegetables. I remember big red radishes, the hot horse radishes, and the delicious small new potatoes that were dug up early in the season before the potatoes were full grown.

My grandfather’s ancestors had come over to Canada from Ireland around 1850 during the potato famine.

During potato planting in the springtime, each potato was cut into sections so that a couple of potato buds were available to grow a new plant. All of the cut potato pieces were dipped in a solution of copper sulfate in order to kill fungus, a tradition passed on through the family for generations. Needless to say that during my years on San Juan, we Irish descendants ate potatoes in one form or another three times a day.

Both my parents and grandparents bought only a few basic items regularly from the store, such as sugar, coffee, flour, and salt. My grandfather also bought big salt blocks, which were licked by the salt-craving cattle. I don’t remember that we ever bought napkins except on the main holidays. We didn’t buy toilet paper either, because the old Sears catalogs served the purpose in the outhouse since the pages were just the right size and texture.

When our shoes wore out, we bought new soles and heels from the local shoe repair shop or through mail order from Montgomery Ward or Sears & Roebuck. We nailed the new soles and heels on using our own shoe repair equipment. Whenever we had a flat tire – and that happened often since the rubber was inferior to today’s rubber products – we removed the flat tire from the wheel and fixed the inner tube ourselves.

With policies established by President Roosevelt, the state also supplied money to the county for various social services. For example, Friday Harbor High School offered boys a three-month course in blacksmithing. The local blacksmith, Mr. May, who happened to live two doors away from us, taught a beginning blacksmith course. About a dozen boys signed up to learn how to mold iron into various shapes.

I was able to take a block of iron, heat it up over a coal fire until it turned from red to almost white. That feat was achieved by blowing hot air through the burning coal, which increased the heat output. The white-hot metal was then soft enough to pound into the desired shape, which for me was a one-pound hammer. With further working of the metal, I punched a hole through the middle, large enough to insert a hardwood handle. For farm boys, the course was ideal because it gave them some idea of what a blacksmith could do to repair farm machinery.

The Depression didn’t end until America began gearing up for World War II, when more than 10 million able-bodied young men were drafted. Other able-bodied young people then readily found jobs and the economy began to recover. The government activities created by Roosevelt hadn’t really brought back prosperity.

Despite the Depression, the farmers on San Juan Island, especially those with sizable acreage, readily survived.

— Andy Hansen was born on San Juan Island in 1920. He left farm life as a young adult to attend the University of Washington, eventually graduating with a master’s degree in chemistry. He is now a retired chemist and a freelance writer. One of his recent articles was published on www.tcsdaily.com. He lives in Laguna Niguel, Calif., with his wife of 60 years. His blog, www.grandpa-andy.blogspot.com, depicts more of his life on the farm on San Juan Island.