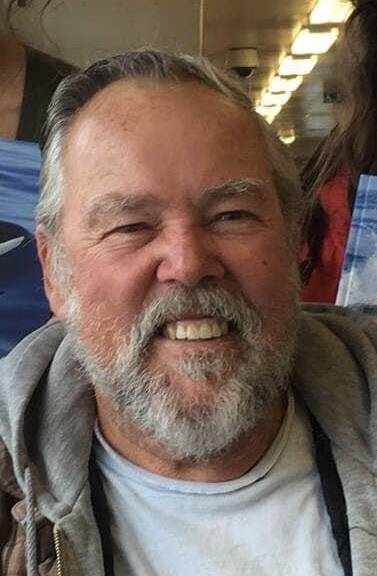

Kenneth “Ken” Chester Balcomb III – a tenth-generation Balcomb – died peacefully in his sleep on Dec. 15, 2022 surrounded by loving family at the Center for Whale Research’s “Balcomb Big Salmon Ranch” above the shores of the Elwha River near Port Angeles, Washington.

Ken was born Nov. 11, 1940 in Clovis, New Mexico to father Kenneth Chester Balcomb II and mother Barbara Jean Bales. Ken is survived in life by his son Kelley Balcomb-Bartok and his wife Carlene Balcomb-Bartok, granddaughter Kyla Balcomb-Bartok and grandson Cody Balcomb-Bartok, brother Howard Garrett and wife Susan Berta, brother Scott Balcomb and wife Janet Collins Balcomb, brother Mark Balcomb and wife Lisa Balcomb, uncle John Douglas “Doug” Balcomb and wife Cecelia Balcomb, cousin Stuart Balcomb and wife Joanne Warfield, nephew Stephen Spencer “Bo” Balcomb and wife Janet Goslin Balcomb, nephew Samuel “Sam” Richard Balcomb and wife Kimi Balcomb, nieces Jennifer Ruth “Rue” Balcomb, Jennifer Goolsby, and Jessica Chapman, as well as many grand-nieces and nephews. Ken is predeceased by his mother and father, brother Richard “Rick” Garrett, sister Katherine “Kathy” Balcomb Rippy, and uncles Edward and Samuel Balcomb.

Ken spent his early boyhood growing up in Albuquerque, New Mexico before moving to Carmichael, California, just north of Sacramento, in 1951. He graduated from San Juan High School in 1958, attended American River Junior College in Sacramento before graduating from the University of California, Davis, in 1963 with a Bachelor’s degree in Zoology and a budding interest in marine mammals.

Ken embarked on his lifelong pursuit of first-hand education about whales by volunteering as a dishwasher on a whale catcher boat operating from San Francisco Bay in late 1963, and was soon hired by the US Fish & Wildlife Service as field biologist in a whale marking program in the eastern North Pacific Ocean. Between whale marking expeditions in 1964 and 1965, Ken attended graduate school in Zoology at UC Davis, while working as a biological technician at the Richmond, California whaling stations, collecting data and specimens for the National Marine Mammal Laboratory in Seattle. It was during these early whale tagging operations that Ken purchased his first Nikon camera, which began a lifelong passion for wildlife photography.

In 1966, Ken was field biologist for the Pacific Ocean Biological Survey Program of the US National Museum, banding and studying seabirds in the central North Pacific. From 1967 to 1972, Ken served as lieutenant in the US Navy as aviator and anti-submarine warfare specialist. During his Naval service Ken was awarded a National Defense Service Medal, Meritorious Unit Commendation. While working on a then-classified passive sonar submarine detection system known as SOSUS (Sound Surveillance System), Ken discovered and became fascinated with the undersea world of sound, especially whale vocalizations.

Ken took a one-year break from the Navy to attend graduate school in Marine Biology at UC Santa Cruz to study under the tutelage of Professor Kenneth S. Norris, a world-renowned marine mammal biologist, conservationist, and naturalist who did pioneering work on dolphin echolocation.

Ken temporarily worked for the Fisheries Research Board of Canada as visiting biologist at whaling stations in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia before returning to the US Navy for a two year tour as instructor of military oceanography and acoustics in Japan. During his time in Japan Ken visited all of the operating whaling stations on Honshu and Hokkaido, and did a study of Baird’s beaked whales.

Beginning in 1976 Ken immersed himself in benign studies of living whales on both coasts of the North American continent: In the Pacific Northwest Ken contracted with the US government to provide a detailed photo-identification census of the killer whale population in Washington State waters; while on the east coast Ken became the Research Director for the Ocean Research & Education Society (ORES) based in Gloucester, Massachusetts, with emphasis on the emerging methodology of photo-identification of humpback whales in the western North Atlantic from Newfoundland to the Dominican Republic. Research was conducted aboard the Regina Maris, a 144’ Barquentine sailing ship owned by friend and colleague Dr. George Nichols.

In the spring of 1976 Ken founded and directed the killer whale photo-identification study “Orca Survey,” based on Dr. Michael Bigg’s then-unprecedented methods established in the early 1970s. The photo-id study was contracted under Dr. Dale Rice of the National Marine Mammal Laboratories in Seattle, who Ken originally worked for during his whale tagging operations at the Richmond Whaling Stations in the 1960s.

The purpose of the original photo-identification study of Killer Whales in Washington waters was to assess the existing killer whale population plying these waters, and determine if the population numbers could sustain further captures. For nearly a decade prior (1965-1976) captures of killer whales for display in aquariums and marine parks around the world primarily removed the calves from the Southern Resident killer whale (SRKW) population. Ken’s initial research census unequivocally showed the SRKW population could not sustain further captures and removals, forever ending captures in the US.

For Ken, his passion for whales was infectious, and his desire to share his enthusiasm for whales–both living and dead–was evident throughout his life. Just three years into his early work studying the Southern Resident killer whales, Ken charmed his way into Lee Bave’s heart–and the second floor of her Oddfellows Hall building in Friday Harbor–to found The Whale Museum. In 1981 Ken established a Whale School based out of the Turn Point lighthouse on Stuart Island. In 1984 Ken founded and directed the Center for Whale Research which continues to maintain one of the longest and the most comprehensive photo-identification studies of killer whales in the world.

In 1986 Ken teamed up with Earthwatch–an international environmental charity that supports hundreds of research projects across dozens of countries–to provide volunteers the opportunity to engage directly in scientific field research alongside leading scientists at Orca Survey. These research expeditions, spanning over twenty years, provided hundreds of people from around the world the experience of participating in all aspects of the unique photoID project. Many Earthwatch participants went on to become passionate advocates and ambassadors for whales–especially the Southern Resident killer whales–following their experiences with Ken, Dr. Astrid van Ginneken, and others.

As a life-long whale biologist, Ken wished to be remembered for his rediscovery in 1966 of a Fraser’s dolphin, Lagenodelphis hosei, thought to be extinct and only previously known from a carcass discovered on a Sarawak beach in Malaysia back in 1893. Ken also observed the first living specimen of a Longman’s beaked whale, Indopacetus pacificus, also known as the tropical bottlenose whale, or the Indo-Pacific beaked whale. Both species were observed the same day deep in the Pacific Ocean during a bird banding survey for the Smithsonian Institution. Both species were located where the international date line crosses the equator, and Ken of course snapped the first definitive photos and carefully documented both discoveries.

Ken often saw the potential for educational outreach in disparate locales, including a display depicting dolphins and beaked whales in Hopetown, Bahamas, and in Huatabampito, Mexico, where residents extracted and articulated a buried sperm whale skeleton. In addition to founding The Whale Museum, the Center for Whale Research currently educates the public through the Orca Survey Outreach and Education Center opened in downtown Friday Harbor in 2018.

Ken didn’t seek controversy but when his study whales were harmed by human activities he felt compelled to apply his factual knowledge to help guide mitigating changes.

In 1994, when asked to devise a way to rescue Keiko–the star of Free Willy–from near death in an inadequate display tank in Mexico City, Ken proposed Keiko’s rehabilitation in a sea pen and ultimate return to his native Icelandic habitat. Ken was first criticized for proposing the idea before the concept was ultimately successfully enacted.

In 1995 Ken stood beside Washington Governor Mike Lowry and Secretary of State Ralph Munro to announce the launch of a campaign to return the last surviving orca captured before 1976 from an unlawful display tank in Miami. (At the time of Ken’s death an unlikely series of events has occurred that present the real possibility that she may indeed soon return to her native waters in the Salish Sea).

In another incident, a mass stranding of beaked whales in the Bahamas in 2000 took place while Ken was there studying the same population. Ken documented the events from his perspective as both a cetologist and a veteran of naval anti-submarine warfare, and it soon became clear to him what had happened. The ensuing investigation and litigation determined Naval sonar operations caused the strandings and ultimately led to tighter controls on Navy sonar operations worldwide.

Similarly, when a navy destroyer used powerful, mid-frequency sonar in Haro Strait on May 5, 2003 while Ken was conducting photo ID studies of J pod of the Southern Resident orca population, Ken’s extensive video and audio documentation of the events provided irrefutable evidence of the cause and harm of the incident.

Ongoing population studies conducted by the Center for Whale Research under Ken’s direction documented the steep decline in SRKW numbers from 1995 to 2001, ultimately leading to the listing of the population as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 2005.

Based on scientific evidence, Ken and a wide consensus of the scientific community realized that the primary cause of the decline was malnutrition due to decreases in Chinook salmon populations, and that removal of the four lower Snake River dams, along with a wide range of salmon restoration efforts, could help provide needed sustenance for the struggling orcas. Ken’s advocacy for salmon protection and restoration took its toll on him, however, and became a distraction from his fundamental demographic studies.

Serendipitously, an opportunity arose to acquire property alongside the newly restored Elwha River, offering a way for Ken to highlight a highly successful restoration project as a way to fulfill his mission of research, education, and conservation on behalf of his beloved orcas, at the Center for Whale Research’s Balcomb Big Salmon Ranch.

In lieu of flowers, Ken may be remembered by contributing to the Center for Whale Research (www.whaleresearch.com) to support the work to carry on Ken’s life and legacy.