As spring approaches, the San Juan Islands Museum of Art is preparing to premiere three dynamic exhibits. One focuses on culture, diversity and the symbology of water, the other two pay homage to the numbers of missing native women.

The exhibits “Missing” and “Highway of Tears,” featuring Vancouver, British Columbia, artist Deon Venter, opens March 6 in the Nichols Hall and runs through May 25. “The Pulse of Water,” featuring Seattle artist June Sekiguchi, opens March 26 in the atrium and runs through May 25. Both artists are internationally known, with exhibits shown across Africa, Asia and Europe.

“Missing” and “Highway of Tears”

“In my family, it was said I was drawing before walking, so I probably had a natural affinity for expressing myself visually rather than verbally,” Venter said.

Venter’s expression has recently focused on the missing and murdered native women around the Vancouver area.

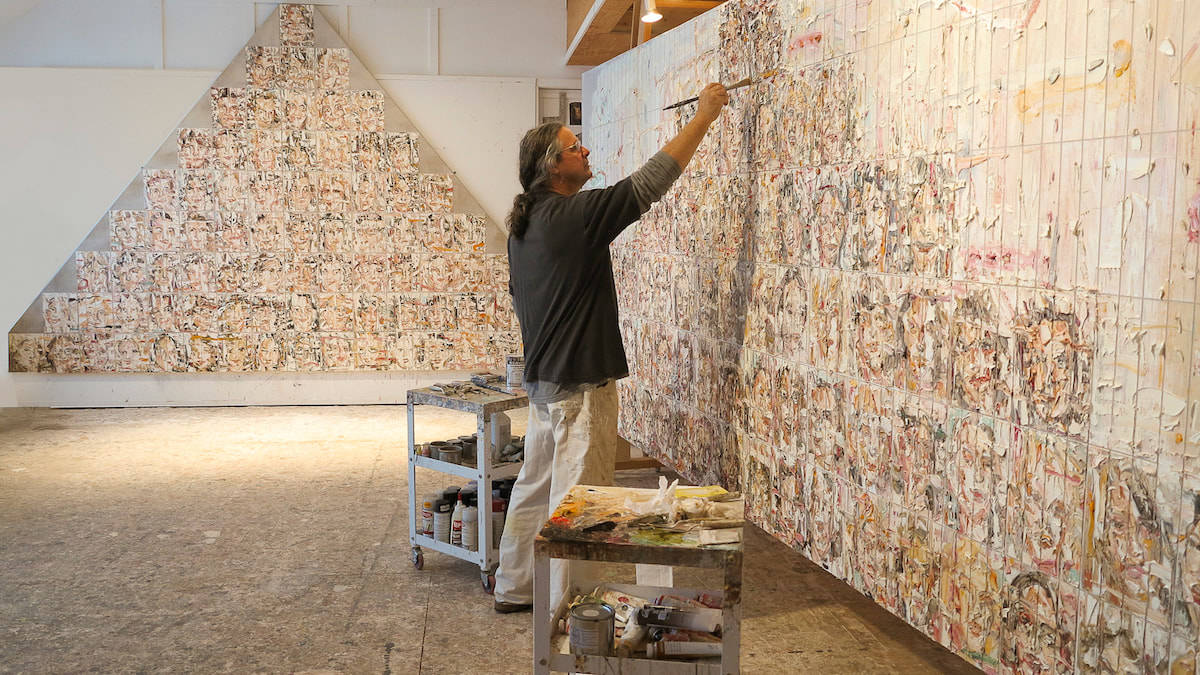

“Missing” features large, 9-by-15-foot oil paintings. Each piece represents one of the estimated 120 women who have been murdered or have disappeared within a two-block radius of Vancouver’s downtown eastside. The women have primarily been involved in the sex trade, according to Venter, and a disproportionate number of them Aboriginal.

Some of the portraits are shaped in pyramids, which Venter explained was inspired after deconstructing the image of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” in a quest to see what made it such a successful composition. Artists built pyramidal compositions, Venter noted, to evoke a powerful response in the viewer.

“Pyramidal paintings, in a way, eliminate the compositional need because the canvas itself is the pyramid,” Venter said. It allows him to present the painting in the chronological order that the women went missing, he explained.

“As tragic as the deaths of these women are, united in their circumstances, their legacy is a powerful and collective voice and this is the intended empowerment I bring to the paintings in the ‘Missing Series,’” Venter wrote in a press release about the exhibit.

“The women from the Vancouver downtown eastside were all in the sex trade. As one [woman] pointed out, nobody starts out wanting to make the sex trade her profession,” he told the Journal. “It is circumstances and exploitation which drives them into this vulnerable position. It can happen to anyone. The experiences of these women are incomprehensible and inhuman.”

Through the compositional paintings, Venter continued, he attempts to give these women a voice reaching the scale of their tragedy.

“It is an indictment to all of us — it happened under our watch with very little public outcry,” said Venter about the ongoing disappearances of First Nations women in Canada. “Although we are no Willie Pickton, as Canadians we find ourselves in the court of public opinion for our inaction.”

Pickton is a Canadian serial killer who was convicted in 2007 of the second-degree murders of six women.

“I’ve learned that despite their circumstances, how resourceful and creative these women were,” Venter said. “Camaraderie and excitement were a part of their lives.”

The “Highway of Tears” highlights the short stretch of Highway 16 between Prince Rupert and Prince George, British Columbia, where 18 girls, almost all Aboriginal, have been murdered since 1969.

“The women who vanished from Highway 16 were all teenagers hitchhiking to neighboring towns when they were preyed on,” Venter said.

The installation is comprised of individual portraits intermingled with flower paintings. Venter said he was inspired by two poems of the Pulitzer Prize-winning American poet Mary Oliver, entitled “Goldenrod” and “Peonies.”

“Whenever I travel Highway 16 I am amazed by the sight of the goldenrod [flower]. … Mary Oliver so beautifully describes the delicacy and vulnerability, but also the possibilities. As we pluck these flowers, so were these young women whose lives wereended prematurely,” Venter said, adding that he hopes people stop and think what if it was their daughter, mother, sister or wife.

When asked what individuals could do to solve the issue, Venter replied, “Firstly, men are the perpetrators and they have to look in the mirror. Secondly, the sex trade should be legalized to offer some protection for these women. Thirdly, free bus services in rural areas to prevent young women from hitchhiking.”

Venter added that society as a whole needs to encourage respect for women and minorities from a young age and curb the objectification of women.

“A historical synopsis of these two tragic events is inadequate, but, in the views of many, they speak to the systemic violence against women worldwide,” Venter said.

“The Pulse of Water”

“I have always identified as an artist from my earliest memories,” Sekiguchi said.

Sekiguchi began creating mixed media collage pieces after becoming fascinated with manipulating materials like wood into unusual forms.

“There is a lot of problem-solving in physically making the work sculptural from literally the nuts and bolts, to how it stands or hangs,” she explained.

Water — rivers in particular — plays an important role in her work. Sekiguchi’s “The Navigating Series” was inspired by rivers she has seen during her global travels. That series expanded into a waterfall river wall installation, according to Sekiguchi, which was shown in six different exhibitions in Washington.

“Pulse of Water ” features a bamboo footbridge with a sculpture symbolizing a river, specifically the Mekong, flowing beneath.

Sekiguchi has visited Laos four times in the last 14 years. During her first visit, she took a longboat on the Mekong River.

“In that meditative journey, I saw ripples and swirls on the sienna colored surface and thought of all the unseen things underneath causing the action,” Sekiguchi said. “I saw that as a metaphor to our human selves.”

People’s experiences and stories make them who they are, Sekiguchi continued, yet their past is not seen. The eddies and swirls of the river’s water represent those hidden tales, she explained.

According to Sekiguchi, the Mekong is often called the Mother of Rivers and serves as a lifeline to the country. She metaphorically likened the river as the Earth’s bloodline — indicating the health of the environment, and taking the pulse of human health. Both China and Laos have dammed the Mekong extensively, Sekiguchi said. This has depleted the river, causing devastating environmental effects on livelihoods such as farming and fishing downstream in countries like Cambodia and Vietnam.

“I equate the dams to blocking of arteries, which is harmful to the body,” Sekiguchi said.

Sekiguchi explained that her art, in its repetitious physical labor, honors the themes of family, history and culture.

“My work intensely manipulates materials and is time consuming,” she explained, which helps her address and process pivotal experiences in her life, like the passing of loved ones, or other times of crisis, as well as rites of passage. Through her work, Sekiguchi added, she is able to exercise the aesthetic and conceptual influences of her Japanese heritage.

“My studio practice is a way to honor these most important events, people and experiences in my life,” Sekiguchi said.

In keeping with paying tribute to important events, the footbridge in the exhibit represents a real bridge that spans a tributary of the Mekong called Nam kan.

“Each year the monsoon rains wash the bridge away. Each year the people rebuild it. It is a metaphor for the Buddhist ideology that everything in life is temporary,” Sekiguchi said. “The rebuilding of the bridge is an act of devotion to the concept of impermanence.”

For more information about the art museum, current exhibits and upcoming exhibits, visit https://sjima.org/.