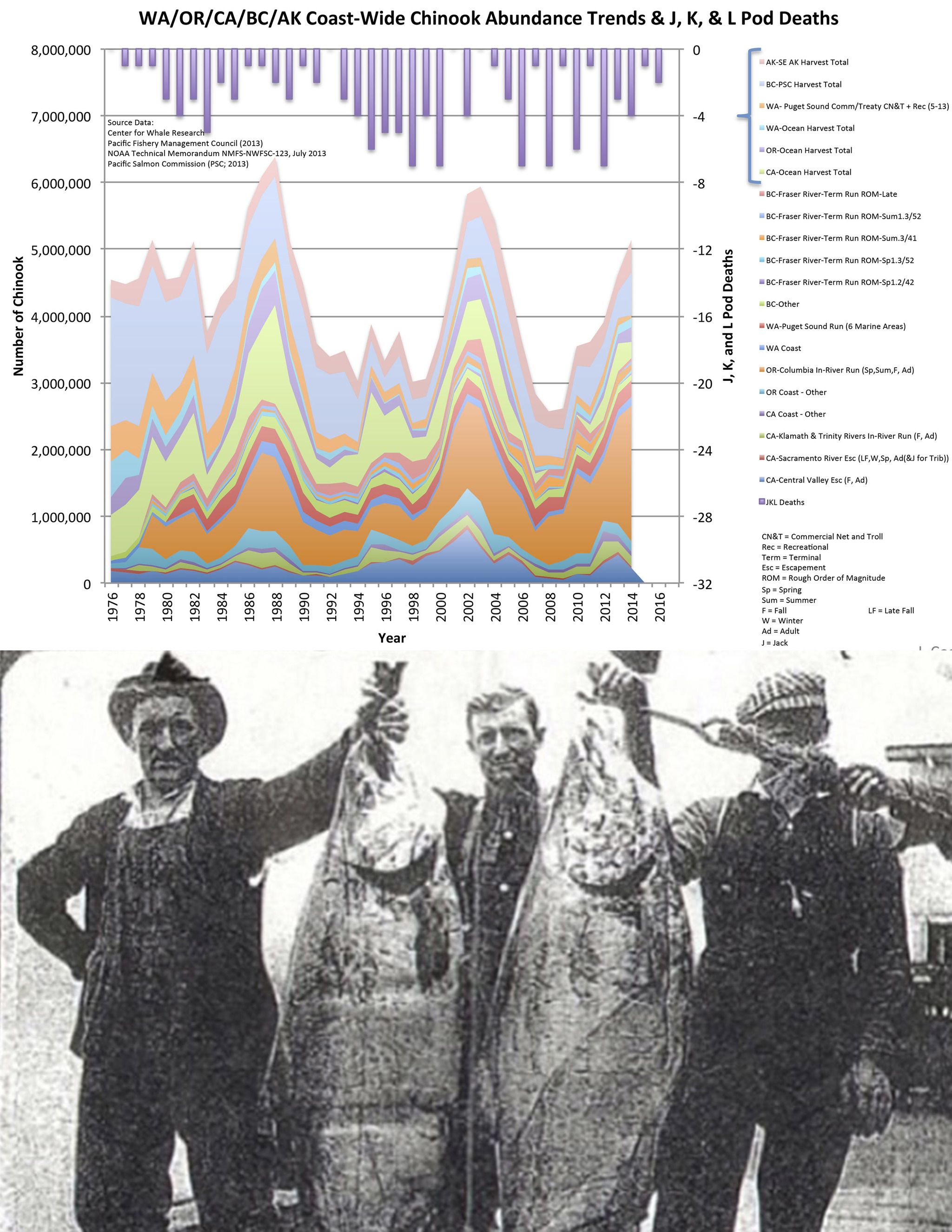

Once tipping the scales at over 120 pounds, Chinook salmon have always been the staple of Southern resident orca whales, according to Deborah Giles, research director and projects manager for the Center of Whale Research.

“Today we think a 30-pound Chinook is big,” Giles said, pointing out an old photo of two fisherman in Astoria, at the mouth of the Columbia river.

The men are holding up a photo of a pair of fish, which appear to be more than four feet long, and easily weigh 110 pounds.

“These are what the southern residents evolved to eat,” she added.

According to Giles, these salmon eaters pretty much stick to Chinook.

“They don’t really know what to do with pinks or humpies [pink salmon or humpback salmon]; it’s almost like they don’t register them as fish,” Giles said. “Calves will sort of mouth them, but they don’t really eat them.”

She said studies on orcas’ fecal matter have backed up these observations. Only one Northern resident orca, the salmon-eating orcas in Canada, showed signs of eating a pink salmon once, she said.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s website lists many salmon species, including Chinook, as threatened and endangered. As a major source of the residents’ diet, this does not bode well.

Chinook are facing habitat loss, overfishing, pollution, global warming, ocean acidification, harmful algae blooms, and a general oceanic ecosystem collapse due to ocean temperature shifts, according to Rich Osborne.

Osborn is the former executive director of the Whale Museum, restoration ecologist at the University of Washington Olympic Natural Resources Center in Forks, and is the program director for the Washington Coast Sustainable Salmon Partnership.

Part of the reason for decline of the 2016 runs, according to Osborne, is a severe warm water pattern in the Pacific Ocean that lasted from 2013-2015, nicknamed, The Blob.

“The Blob moved prey and disrupted salmon routes for the ocean migrants during that period, affecting those year classes of adult salmon,” Osborne said, “The fish starved those years.”

He went on to explain that The Blob’s impact will continue to be felt for the next couple of years. Chinook runs were extremely low in 2012, and there were very few sightings of J, K and L pods that combined, make up the travel groups of the Southern resident population. Pods usually consist of five to thirty whales.

This year, Chinook runs are predicted to be even lower than 2012, and according to Giles, as of mid July, only a few matrilines, (mothers and their offspring) amounting to 10 individuals, have been spotted in inland waters.

According to Giles, when there are coast-wide shortages of Chinook there are more Southern residents deaths. In 2012, seven whales were lost.

“They are breaking into smaller and smaller groups because there isn’t enough salmon to share with their normal larger groups,” Osborne explained, “they are not following normal patterns because they are on a desperate search for salmon anywhere they can to find them.”

The infamous whale board, showing visitors when whales were last seen at Lime Kiln Park, is dotted with week-long stretches of Southern resident absences. Last year’s board showed only two or three-day absences. This behavior has Ripon College Professor Bob Otis, who has lead research at Lime Kiln Park for decades, and his researchers concerned. To help educate, researchers have been giving information to park visitors about ways individuals can help.

“We love it that people come out to see the whales,” said Rylee Jensen, a researcher back with Otis’ team for the second year, “I wish that they would make the connection this is a special, and endangered group of whales.”

She added that when the resident whales were listed in 2005, the population was 85, compared to this year’s count of 83.

Traffic

Mark Anderson, founder of Orca Relief, a nonprofit organization working reduce cetacean mortality rates, in 1997 due to the orcas’ dwindling population. He cites studies from biologist Dave Bain and others, showing that when vessel traffic is present, orcas’ metabolism goes up, they take deeper dives, and echo-locate louder to be heard over motor noise. As a result, Anderson said, Southern residents need to eat 17 percent more when they are already struggling to find enough food.

The dam

In an attempt to help bring Chinook back from the brink, many researchers are calling to breach four dams in the lower Snake river, opening up more spawning ground. The Snake river, according to Giles, is ideal because it has the highest elevation and coldest water of river systems in Washington – cold water being a key feature for salmon to thrive in. The Snake also feeds into the Columbia river, which was once one of the world’s largest salmon-producing rivers according to Giles.

“Historically, Columbia Chinook were probably the Southern residents’ mainstay.” Osborne said, adding that they are still an important part of orcas diet.

Tagging data backs this up. Giles said tagging results show Southern residents frequently loop by the mouth of the Columbia.

Anderson agrees that breaching the lower Snake’s dams would be helpful, along with any Chinook restoration. He is concerned that results from those efforts could take 20 years or more, and fears the whales may not have that much time to wait.

“Requiring whale watch boats to stay further back especially along the west side [of San Juan] would have an immediate impact [in helping orcas hunt,]” Anderson said. “We could see an improvement today.”

The west side is singled out, he said, because with deep water and steep rocks to trap the salmon, it is prime hunting ground.

So far this year, they are barely using that prime hunting ground; instead, an abundance of humpbacks, minkes and transients have been seen throughout the islands.

The transients

Transients are the marine mammal-eating orcas, who hunt seal, sea lions and porpoise.

“If we were to begin researching orcas today, we would think the transients were residents, the ones that lived here, and the residents were transients, only occasionally cruising through,” Giles said, explaining that the baseline for orca research in the Salish Sea is shifting.

Transients, the marine mammal-eating orcas, are currently doing well, despite the fact that due to being higher on the food chain, they have a higher toxin level than the salmon-eating residents. This, according to Giles, is because seals, sea lions and porpoise are all at record population levels giving transients plenty to eat. During fasting and famine situations, when the animals are using the blubber where the toxins are stored, is when problems like suppressed immune systems occur. That, according to Giles, seems to be what researchers are seeing, “If Southern residents had enough food, it [toxins] still would not be good, but it wouldn’t be as bad of an issue,” he said.

Babies

The recent resident orca baby boom does not give Giles much comfort.

“K pod has not had any babies since 2011,” Giles said, and while eight of the calves have so far made it, one has not been sighted this summer, and neither has its mother. Giles also pointed out that 13 females were pregnant in late 2015. Two calves died almost immediately, and two more were never seen, Giles said, and possibly either miscarried, or also died soon after birth.

What can we do?

Anderson pointed out that to increase a population, it takes more than counting heads; we must look to the core viable breeding members. That core of Southern residents is getting smaller and smaller.

He is not hopeless however, saying, “We thought minkes were a goner when we began studying them. Whales can come back,” Anderson said.

Osborne also believes orcas are resilient, but “they “need wild salmon that do not require humans and barges to complete their life cycle.”

Hatcheries and fish farms may be a short-term solution, but really only work to provide human food. “By their existence and peripheral impacts, they only hasten the extinction of wild Pacific salmon,” Osborne said.

Giles does not believe hatcheries and farms are a viable solution either. Hatcheries, she said dilute the wild salmon genes, while farms can spread disease, and cause environmental damage due to the constant close quarters of the fish.

“We know what the problems are; we need to make some hard decisions,” Giles said, like perhaps opting to eat Sockeye instead of Chinook.

“We need to spend 100 percent of our energy getting fish into the mouths of these whales,” Giles said.

For info visit The Center for Whale Research at whaleresearch.com, Orca Relief at orcarelief.org, the Whale Museum at whalemuseum.org or at NOAA at noaa.gov.