Osamu Shimomura was 16, living in Nagasaki, Japan in 1945, when the city was bombed. His grandmother made him clean up after he returned home covered in atomic grey ash. He credits her and that bath for saving his life. If he had not survived, modern chemistry and medicine would be vastly different today.

“Shimomura’s research is an example of how questions based on curiosity about the world can lead to answers with great practical benefits,” said Richard Strathmann, resident scientist at the UW Friday Harbor Marine Laboratories. Shimomura passed away Oct. 19, 2018, but his legacy in science will be remembered.

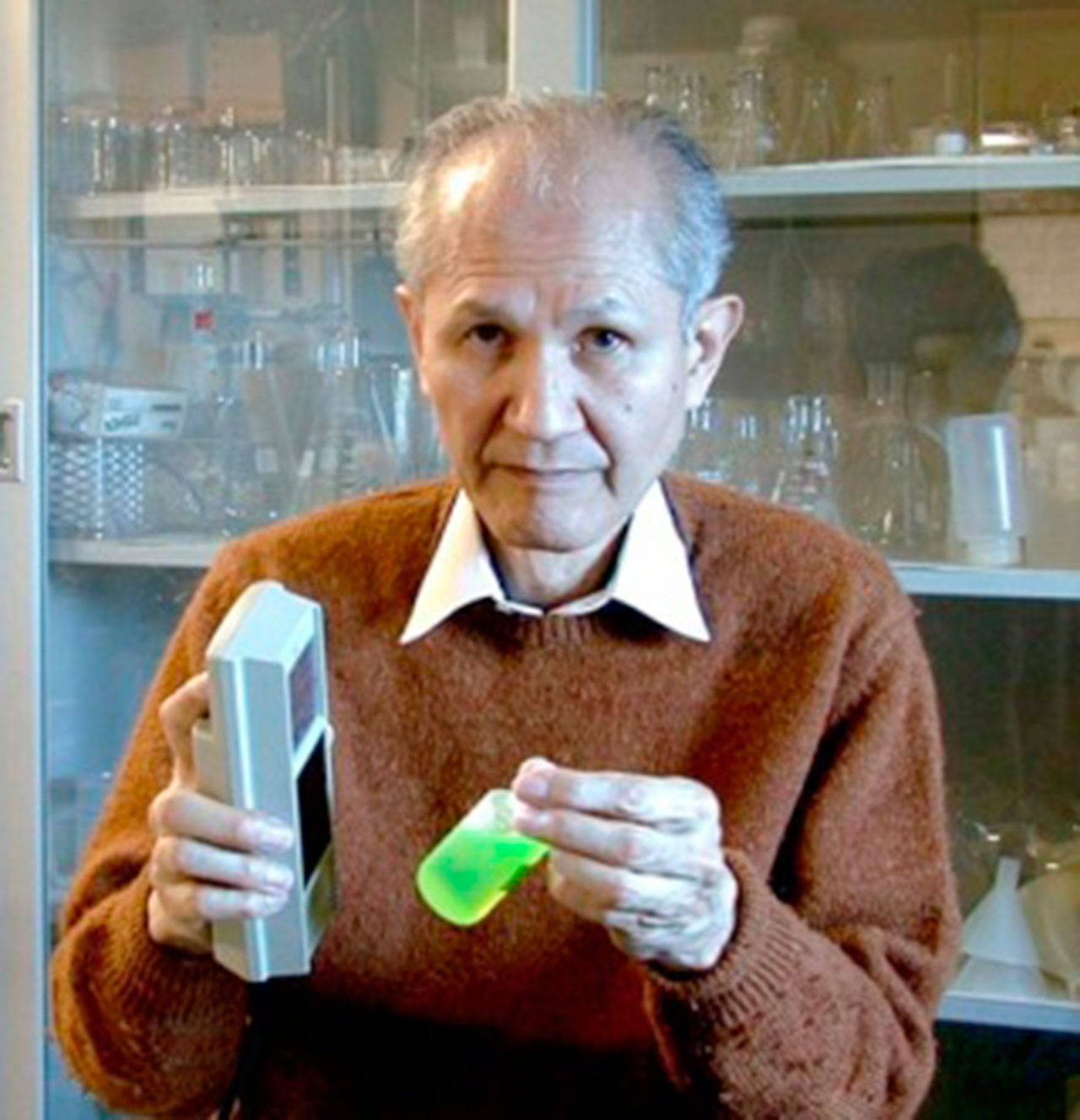

Shimomura won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2008, for his research on aequorea jellyfish and the discovery of green fluorescent proteins. Those proteins have since been modified for use in medicine. It is injected into cells allowing doctors to spot anomalies, a technology used in cancer detecting.

Frank Johnson, a Princeton professor, invited Shimomura to study jellyfish at the Friday Harbor Labs. From 1961 to the 80s Shimomura collected jellyfish and their fluorescent proteins. He hired local students, including Liz Illg, whose parents worked at the labs, to assist him.

“It was a lovely job,” she said, noting that Shimomura was a very polite and proper man, in contrast to his collaborator Johnson, who was quite a goofball.

Shimomura described arriving at the labs in his biography:

“The scenery of San Juan Island was splendid. The sea was clean and beautiful. At low tide there were colorful sea urchins and starfish in various sizes scattered on rocks and abalone. There was also abundant fish. We could easily get rockfish … using simple lures. We often ate them as sashimi. “

Shimomura, Johnson and their young crew would go out in his Boston Whaler and collect jellyfish with buckets, Illg said. On a good day they could collect thousands of them. The teens would cut what Illg described as rings off the jellyfish. These rings where the fluorescent proteins are stored are located where the legs meet the body of the jelly. They were paid pennies per jellyfish.

“At the time, so far as I could tell, the research was curiosity driven. The question was how do the animals make light,” Strathmann explained, adding that no one expected such enormously extensive practical applications or a Nobel prize would result from such research.

Shimomura returned to Friday Harbor much later and was dismayed that the aequorea jellyfish population had severely declined.

“If the disappearance of the jellyfish had occurred 19 years earlier, we wouldn’t have been able to learn the mechanism of the aequorin bioluminescence reaction,” he wrote.

Jellyfish researcher and longtime islander Claudia Mills, who discovered the decline, has been motoring the situation and stated that there are still aequorins, but the population has not significantly grown.

“Shimomura was very dedicated to science, and I am really glad his hard work was recognized by the world,” Illg said.